4 Educational Philosophies

- 4 Educational Philosophies Relate To Curriculum

- Major Educational Philosophies

- Six Philosophies Of Education

- 4 Educational Philosophies Relate To Curriculum

- 4 Educational Philosophies

- Educational Philosophies Pragmatism

- 4 Types Of Educational Philosophies

After submitting my answers to Group Discussion 2, I started reading the educational philosophies. I tried to follow how I was supposed to do the learning activities by answering all the study questions for each philosophy one by one.

4 Educational Philosophies Relate To Curriculum

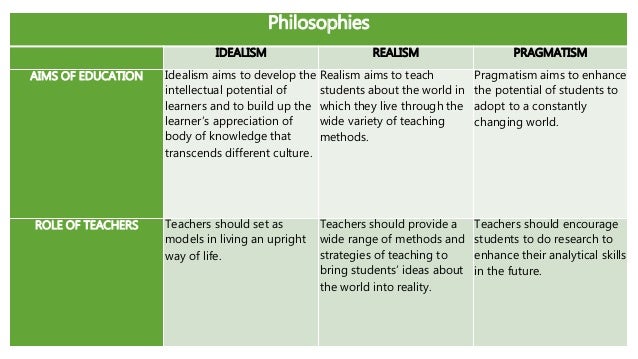

That said, read on to learn about the various educational philosophies in existence. Perenialists tend to believe that the aim of education should be to make students understand the ideas of Western civilization. They think these ideas can solve all problems. Education is life education is growth education is a social process education is a reconstruction of human experiences. Four major philosophies naturalism idealism realism pragmatism 1. Forms of naturalism biological naturalism psychological naturalism sociological naturalism romantic naturalism 1. A student-centered approach to education. A focus on active learning. High expectations for yourself and your students. Your ideal learning environment. Your approach to technology in the classroom. How you motivate your students. Your approach to assessment. Here are 57 teaching philosophy statement examples that you could get some ideas from. The basic philosophies of education are Perennialism, Idealism, Realism, Experimentalism and Existentialism. They are based on a view of society and what is important, as well as political beliefs to a degree. A combination of several of these philosophies or approaches may be the best route to take.

The first reading is the ” Philosophical Roots of Education”. This reading provided an opportunity to review what I have learned in module 2 and 3. Both modules 2 and 3 discussed world philosophies, so I thought of them, although separated by modules, as of the same category, world philosophies. However, the ones that I was able to review using the first reading were the Western philosophies only. I was able to finish and answer the study guide for Module 4A as I was already familiar with the topic. I would say that I used both bottom-up approach and top-down approach of reading alternately. When I couldn’t understand a particular word, I used the top-down approach where I looked at the content and the words surrounding the word I didn’t know so as to get the meaning of the sentence as a whole. In short, I used the interactive approach of reading. The schema theory was also in action as I was reading the educational philosophies as all these philosophies are all connected or related to the world philosophies in module 2. While attacking this learning task, I tried to apply all the things that I know about learning strategies and reading strategies with the purpose to effectively learn what I needed to learn.

After reading the first reading, I then moved to read the readings for Essentialism and Perennialism. According to the reading, Essentialism is the educational philosophy of the conservatives. Essentialism holds the view that the goal of education is to teach what are essential for the learners to learn. Simply put, they believe that the ” basics” should be taught to the learners. Perennialism on the other hand holds the belief that the goal of education is to teach evergreen ideas that have stood the test of time.

Major Educational Philosophies

Essentialist and Perennialist can be a Realist and or Idealist in the sense that both philosophies hold the belief that schools’ aim is to transmit the accumulated knowledge and traditions of the past. While these educational philosophy also agree with the Perennialist assertion that ideas that have stood the test of time are worth teaching for, Essentialist also believe that there are certain core or ” basics” that learners should learn. Hence, this Essentialism stresses the fundamentals or the basic skills. These fundamentals are skills of reading, writing and arithmetic. Children according to this philosophy should learn arts, reading, writing, spelling, measurement, computation in elementary school.

Both Essentialism and Perennialism believe that learners should master the subject matter given of a given grade before going to the next grade. Simply put, they believe in pass or fail system of grading. If you pass, you can move up, if you fail, you have to stay at the level you are in. Reading this, I remember myself when I was in elementary. When I was a child, it was put in my mind by my parents that staying at the same grade level is a shame, so I should study hard, and I did.

Moving on, the desks in Essentialist and Perrenialist teachers’ classroom are arranged in rows, and the seating pattern are in rows. This seating arrangement discourages pupil interaction. Moreover, these educational philosophies also believe in rules and penalties to control students. This reflects that the teacher in Essentialist and Perennialist classroom are the center in the classroom. As the teacher is the centre, he/she is the most knowledgeable person in the classroom. When I was in elementary, this was the seating arrangement we had. My teacher came to our house to tell my mother that I talk a lot during lesson. I was scolded. The following day, I was scolded again because I raised my hand not because I wanted to answer the question from my teacher but because I asked her a question. As a child, I liked asking my teachers about things that were not in the lesson. This was not welcomed. In fact, I was discouraged to ask question.

They favour lecture as a teaching method wanting the students to master the subject. To assess they use recitation. They use objective test such as true or false, multiple choice, completion and others. As such, the textbook is the most useful teaching tool for the essentialist teacher. Reading about Essentialism and Perennialism reminded me one of the Japanese teachers I worked with a few years ago. While I focus on the communicative aspect of language teaching when I teach, when this teacher focused on the grammar or on the structural part of language learning. This teacher just taught grammar and literally kept on talking from the start to the end of the lesson. The class was very silent and most of the students were bored. In short, he focused on the intellectual benefits that learners could get by learning language and not on the functional side of it. I felt like it was kind of off balance, but of course did not say anything about it. I was am I am still and will always be a learner anyway.

After reading about the two teacher-centred educational philosophies, I moved on to student- centered philosophies; progressivism and reconstructionism. Progressivism is the educational philosophy that maintains that ideas should be tested by active experimentation. It has its roots in Pragmatism. On the other hand, Reconstructionism is the educational philosophy that maintains that the quest for the creation of a better society and worldwide democracy. It has its roots in Existentialism and Pragmatism. Upon reading these two educational philosophies, I was able to connect what I do in the classroom as like what Reconstructivist asserts, I believe that my goal when I teach is to contribute to the betterment of the society . I am a language teacher and I focus on the communicative aspect of language. In short, I am more inclined to focus on the practical side and on the experiences of using the language. While a form-focused instruction is substantially important in language teaching, the ability to use the language in authentic situation is of paramount imporatance in my view. Connecting this to Idealism, Perrenialism and Essentialism I think that these educational philosophical approaches are reflected in the Grammar -Translation Method of language teaching. The method of language teaching which focuses on translation, and was used to learn the Latin language so as to be able to read and learn from the classic books like Homer , the Bible and other classic books. In short, like Idealism and Perrenialism, the Grammar -translation method was also more on the theoretical aspect of the language, and not on the experience and practical side of language teaching and learning.

CONCLUSION

Six Philosophies Of Education

In the light of the educational philosophical approaches and connecting all these educational philosophies in my life as a language teacher, I conclude that the underlying philosophies of language teachers can be used as a benchmark against which to measure goals for language learners.

- Problems, issues, and tasks

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Join Britannica's Publishing Partner Program4 Educational Philosophies Relate To Curriculum

and our community of experts to gain a global audience for your work!4 Educational Philosophies

Harvey SiegelEducational Philosophies Pragmatism

Philosophy of education, philosophical reflection on the nature, aims, and problems of education. The philosophy of education is Janus-faced, looking both inward to the parent discipline of philosophy and outward to educational practice. (In this respect it is like other areas of “applied” philosophy, such as the philosophy of law, the philosophy of science, and the philosophy of medicine, including bioethics.) This dual focus requires it to work on both sides of the traditional divide between theory and practice, taking as its subject matter both basic philosophical issues (e.g., the nature of knowledge) and more specific issues arising from educational practice (e.g., the desirability of standardized testing). These practical issues in turn have implications for a variety of long-standing philosophical problems in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and political philosophy. In addressing these many issues and problems, the philosopher of education strives for conceptual clarity, argumentative rigour, and informed valuation.

Principal historical figures

The history of philosophy of education is an important source of concerns and issues—as is the history of education itself—for setting the intellectual agenda of contemporary philosophers of education. Equally relevant is the range of contemporary approaches to the subject. Although it is not possible here to review systematically either that history or those contemporary approaches, brief sketches of several key figures are offered next.

The Western philosophical tradition began in ancient Greece, and philosophy of education began with it. The major historical figures developed philosophical views of education that were embedded in their broader metaphysical, epistemological, ethical, and political theories. The introduction by Socrates of the “Socratic method” of questioning (seedialectic) began a tradition in which reasoning and the search for reasons that might justify beliefs, judgments, and actions was (and remains) fundamental; such questioning in turn eventually gave rise to the view that education should encourage in all students and persons, to the greatest extent possible, the pursuit of the life of reason. This view of the central place of reason in education has been shared by most of the major figures in the history of philosophy of education, despite the otherwise substantial differences in their other philosophical views.

Socrates’ student Platoendorsed that view and held that a fundamental task of education is that of helping students to value reason and to be reasonable, which for him involved valuing wisdom above pleasure, honour, and other less-worthy pursuits. In his dialogueRepublic he set out a vision of education in which different groups of students would receive different sorts of education, depending on their abilities, interests, and stations in life. His utopian vision has been seen by many to be a precursor of what has come to be called educational “sorting.” Millennia later, the American pragmatist philosopher John Dewey (1859–1952) argued that education should be tailored to the individual child, though he rejected Plato’s hierarchical sorting of students into categories.

Plato’s student Aristotle also took the highest aim of education to be the fostering of good judgment or wisdom, but he was more optimistic than Plato about the ability of the typical student to achieve it. He also emphasized the fostering of moral virtue and the development of character; his emphasis on virtue and his insistence that virtues develop in the context of community-guided practice—and that the rights and interests of individual citizens do not always outweigh those of the community—are reflected in contemporary interest in “virtue theory” in ethics and “communitarianism” in political philosophy.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–78) famously insisted that formal education, like society itself, is inevitably corrupting; he argued that education should enable the “natural” and “free” development of children, a view that eventually led to the modern movement known as “open education.” These ideas are in some ways reflected in 20th-century “progressivism,” a movement often (but not always accurately) associated with Dewey. Unlike Plato, Rousseau also prescribed fundamentally distinct educations for boys and girls, and in doing so he raised issues concerning gender and its place in education that are of central concern today. Dewey emphasized the educational centrality of experience and held that experience is genuinely educational only when it leads to “growth.” But the idea that the aim of education is growth has proved to be a problematic and controversial one, and even the meaning of the slogan is unclear. Dewey also emphasized the importance of the student’s own interests in determining appropriate educational activities and ends-in-view; in this respect he is usually seen as a proponent of “child-centred” education, though he also stressed the importance of students’ understanding of traditional subject matter. While these Deweyan themes are strongly reminiscent of Rousseau, Dewey placed them in a far more sophisticated—albeit philosophically contentious—context. He emphasized the central importance of education for the health of democratic social and political institutions, and he developed his educational and political views from a foundation of systematic metaphysics and epistemology.

4 Types Of Educational Philosophies

Of course, the history of philosophy of education includes many more figures than Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Rousseau, and Dewey. Other major philosophers, including Thomas Aquinas, Augustine, Thomas Hobbes, René Descartes, John Locke, David Hume, Immanuel Kant, John Stuart Mill, Karl Marx, Bertrand Russell, and, more recently, R.S. Peters in Britain and Israel Scheffler in the United States, have also made substantial contributions to educational thought. It is worth noting again that virtually all these figures, despite their many philosophical differences and with various qualifications and differences of emphasis, take the fundamental aim of education to be the fostering of rationality (seereason). No other proposed aim of education has enjoyed the positive endorsement of so many historically important philosophers—although, as will be seen below, this aim has come under increasing scrutiny in recent decades.

- key people

- related topics