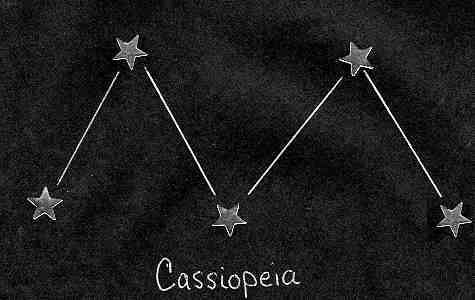

I Cassiopeia

Recently there have been various posts in regards to the validity of various alternative media providers. Come in, share your insights, experiences, feedback and most importantly questions in regards to the many alternative web sites. Cassiopeia sailed from San Francisco 21 December 1942 with cargo for Noumea, where she arrived 12 January 1943. From this base, she offered essential support to the operations in the consolidation of the northern Solomons, carrying the varied necessities of war throughout the South Pacific.

| Look up Cassiopeia in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Cassiopeia (listen; /ˌkæsiəˈpiːə/) or Cassiopea may refer to:

Cassiopea Pharma

Mythology[edit]

- Cassiopeia (Ancient Greek: Κασσιόπεια), also Cassiepeia (Κασσιέπεια), is the name of three different figures in Greek mythology:

- Cassiopeia (Queen of Aethiopia), queen of Aethiopia and mother of Andromeda by Cepheus

- Cassiopeia (wife of Phoenix), wife of Phoenix, king of Phoenicia

- Cassiopeia, wife of Epaphus, king of Egypt, the son of Zeus and Io; mother of Libya

The team behind Cassiopeia's solution-based. Dan is a thought leader, technologist, change agent, and optimist in the area of people experience and the future of work. Cassiopeia was the wife of Cepheus, the Ethiopian king of Joppa (now known as Jaffa, in Israel), and the mother of Andromeda. The queen was both beautiful an. A Survey of Channeling Abortion, Psychopaths and Mother Love Abovetopsecret: Ethics and Google Bombs Abovetopsecret.com, Project Serpo Psy-ops, and the Pentagon's Flying Fish.

Science[edit]

- Cassiopeia (constellation), a northern constellation representing the queen of Ethiopia

- Cassiopeia A, a supernova remnant in that constellation

- Cassiopea, the genus of the 'upside-down' jellyfish

Entertainment[edit]

- Cassiopeia (film), a 1996 Brazilian CGI film

- Cassiopeia (Battlestar Galactica), a TV character from Battlestar Galactica

- Cassiopea (Encantadia), the first Queen of Lireo in the Encantadia fantasy series of GMA Network

- Cassiopeia, the mother of Octavian in The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing

- Cassiopeia, a playable character in the online multiplayer video game League of Legends

Music[edit]

- Cassiopeia (TVXQ), the fan club of South Korean boy band TVXQ

- Casiopea, (est. 1976) a Japanese jazz fusion group

- Casiopea (album), the group's self-titled debut album from 1979

- 'Cassiopeia', a song by Shabütie (now known as Coheed and Cambria) from their 1999 EP The Penelope EP

- 'Cassiopeia', a song by Joanna Newsom from her 2004 album The Milk-Eyed Mender

- 'Cassiopeia', a song by Dragonland from their 2006 album Astronomy

- 'Cassiopeia', a song by Sunny Lax from his 2006 EP P.U.M.A./Cassiopeia

- 'Cassiopeia', a song by Rain from his 2006 album Rain's World

- 'Cassiopeia', a song by Sara Bareilles from her 2013 album The Blessed Unrest

Fictional characters[edit]

- Cassiopeia 'Cassie' Sullivan, a character in The 5th Wave series written by Rick Yancey

- Cassiopeia, a magical tortoise in Michael Ende's fantasy book Momo

Other[edit]

- Casio Cassiopeia, a series of pocket PCs

- Cassiopeia (train), an overnight rail service in Japan

- USS Cassiopeia (AK-75), a Crater-class cargo ship used by the United States Navy in World War II

See also[edit]

- Kassiopi, a village and resort on the affluent north east coast of Corfu

The grass on the Common was long and soft. You could lie down in it, and go to sleep, and people did, with their dogs curled up beside them. If hippies had dozed off in public like that in my suburb in Long Island, the police would have shooed them away, but here you could do whatever you wanted, look however you wanted, stagger around stoned and homeless. I liked that about the town, initially. I was thrilled by the local girls my age, marching down the street on an August afternoon, their backpacks massive, their hair and nails dirty, their legs and armpits unshaved. In my high school there had been a small clique of girls whose clothes and grooming were androgynous, but people screamed at them, teachers belittled them, and the other girls were allowed to throw things at them, as long as they didn’t do it very often. Here, it was normal to look like that. Everything was considered normal, here.

Sometimes, in the sweltering evening, a troupe of bearded men gathered on the Common in tartan skirts and danced to live accompaniment: drums, fiddle, and a flute. They were in their fifties and sixties, and there were easily twenty of them, maybe more. As a crowd gathered to watch, they greeted each other with kisses, hitched up their skirts, and kicked and pranced. In my hometown the elders professed a love of freedom but enforced a simple set of rules regarding how to spend your time, how to maintain your house and yard, how to talk, how to carry yourself, whom to sleep with, and under what circumstances. They would have grumbled at these Celtic gays, and anyway would not have preserved a village green on which a dance performance could be staged. Here you could do whatever you wanted and the townsfolk smiled. Rebellion was impossible.

The result was something that I came to call the illness, in the privacy of my thoughts. Young men and women, bare-armed, tan, circulated slowly through the streets. It wasn’t only that they were idle. It was that they couldn’t stop performing. A girl walked a mountain bike down the sidewalk, improvising a song about a mountain trail. Seated on a bench in front of CVS, a boy in tie-dye beatboxed. A girl sat with her back against the Unitarian church, painting with a Chinese brush on her arm. A few feet away, a boy as young as I was, his button-down slick with sweat, tried to make passersby take an anarchist pamphlet from his hand, calling out, “free newspaper.” If someone acquiesced, he asked for a donation of five dollars, in exchange for six pages, smudged, stapled, and illustrated with stick-figure cartoons. I imagined that, wherever these kids had grown up, they’d found their friends by refusing to conform. They’d belonged to tight little bands of persecuted weirdos. And even if they hadn’t belonged to tight little bands, at least they’d had their persecution, which was a form of attention. Now that they found themselves in a place where nearly all behavior was acceptable, they were lonelier than they’d ever been at home.

I could feel the illness come over me. It didn’t hit me right away, but by the third day of first-year orientation I could hear a change in the way I spoke. In my high school I’d been regarded as unusual because I preferred Raging Bull to Rocky, progressive Democrats to moderate Republicans, Willie Nelson to Dave Matthews. I had friends who felt the same way, three boys and a girl, and the other kids called us the snobs. We walked the halls in a flying wedge, nursing a sense of superiority even as we kept our shoulders hunched and our faces downcast and submissive. Here, a snob was as common as a dandelion, and I began to present myself to the other kids in my dorm as a guy from Long Island; I emphasized the “g” in “Long,” and called myself a guido, neither of which I had ever done before. I wasn’t even fully Italian. Most of my mother’s family was Irish and Czech. But it was a handle to hold: Italian-American Long Islander.

That third day, in the late afternoon, after the orientation activities, I drove out onto the flats near the river, where long white tents shielded a mystery crop from the sun. It was premium tobacco, I learned from my phone. The soil and climate of this New England delta raised the makings of fine cigars. I’d never been to the South, but there was a greenhouse dreaminess here that reminded me of movies where people drawled adages in bowers of live oaks and Spanish moss. Back in Suffolk County, I realized, the grass and trees had the spiky texture of things that grew by the sea. The ocean breezes scoured the land and kept it clean. Here, the woods were thick, the air was half steam. Holsteins stood dazed on the hills that dribbled down to the corn. Everything was calm and cloudy, like the voices of the hippies and the water in the ponds. I stayed in my car, driving fast but in no hurry to get anywhere, singing along to the radio with the AC blasting in my face, a can of Red Bull in my hand.

The following morning, I found a dialogue chalked on the sidewalk. It was at the corner where two fraternity houses, Pike and Delta, lorded over a motel, a Korean church, and the new economics building. The exchange began at the foot of Pike’s wooden Greek-revival porch, in red block letters with purple borders:

Rush Week

Are you in?

Hell yes when is it

Next week chief

The rebuttal was forest green. The letters were tall, straight, and plain, all virtuous simplicity.

Shut down The frats

The system Must die

I’d never given frats much thought. But it was nice to see that there were people who lived here who were hated by some of the other people who lived here.

I mentioned this to Adrienne, a girl in my orientation group. As our sophomore leader drove us from the swimming hole to the Emily Dickinson House to the bakery we sat in the rearmost seat of the van and exchanged complaints about the things we saw, our feet up on the seats in front of us, picking at the nametag stickers on our chests. We’d been struggling to find things to say: How could anyone eat burritos with yogurt in them? How could there be enough terrible people, in this small town, to sustain a typewriter store? She had thick dark eyebrows, olive skin, and shoulder-length hair that was straight and heavy, as if its natural oils had been allowed to accumulate. It made me think of the word “languish.” It was languishing.

“The thing about it is,” I said, “everything here is so, ‘I’m cool with you, you’re cool with me,’ and it’s good to have a break from it. I don’t want to join a frat, but when everybody’s tolerant of everybody else it’s like—” I struggled to explain. “They’re talking past each other.”

Her eyes widened with pleasure. In bringing up fraternities I’d given her something to rant about, and a rant promised to cut through the awkwardness of our conversation. “Fuck those guys,” she said, twirling a blade of grass between her thumb and forefinger. “The thing about them that annoys me most isn’t even necessarily the hating women, because that’s everywhere, it’s that they’ve built these little worlds for themselves where they’re kings of shit.” She was suddenly beautiful and seemed to address the passing scenery, rather than me. “They’re like nerds playing Dungeons & Dragons, calling themselves knights and wizards, but they think they’re these major players. ‘Did you know I’m the grand president of Phi Alpha Epsilon?’ ‘Did you know I’m the hottest guy in the world, because everyone in this house agrees I’m Vice Chancellor of Gamma Zeta?’ It’s the same with sorority girls. ‘I’m not just some girl from Wayland, I’m Queen Cassiopeia of Kappa Delta, and everyone else in this little house I live in agrees that I’m the most significant person of all time.’ It’s like, have fun in your little playpen where you’re all noble rulers of your little turd mountain.” She thrust her hand through the van’s half-open window, released the blade of grass, and flexed her fingers.

The van stopped in front of Barts ice cream. Everyone in the group went inside and lined up beside an old-fashioned gumball machine and a nearly life-sized statue of a cow. “Barts,” said Adrienne. She sneered. “Here in Amherst, they think Barts is what it’s all about.” She listed the ice cream parlors of her native Boston, counting them off, as if the slow recitation of their names—J.P. Lick’s, Toscanini’s, Christina’s, Emack & Bolio’s—might convey the superiority of their product. She shook her head, in a pantomime of melancholy. That was the real thing, she said. Barts was the one choice they had here, so they had to love it. Did we have good ice cream on Long Island?

I wracked my brain. Surely I could come up with a family-owned ice cream parlor, when I really needed one. There must have been some white clapboard shack with a line of parents and children waiting their turn with sandy feet, snaking down toward the Sound or the open sea. There must have been some marble-countered soda fountain with an operatic Italian name or a vaudevillian Jewish one. The problem was that I had only decided a couple days ago that Long Island was important to me. I hadn’t cared about Long Island while I was living on it, so I hadn’t paid close attention to what it was like.

Adrienne stood there looking up at me, neither my superior nor my inferior in magnetism and looks. We emitted the same amount of charge. We were both short, with pink, baby faces, and small eyes. Perhaps this accounted for our loneliness, and therefore our susceptibility to the illness, her shabby Bostonianism and my shabby Long Islanderism. We weren’t ugly. It was just that God hadn’t set us down on Earth to be main characters. Think of a romantic comedy— there’s often a secondary couple, a funnier, less important one, sometimes lustier and more cheerful than the primary but always less graceful, less aristocratic in bearing. We each knew ourselves to be fit for membership only in the secondary couple, I think, but neither of us had been resigned to that fate for long. The knowledge of my secondariness still stung. I felt that my soul was the soul of a main character, but that my mediocre face and body had begun to deform its growth, the way a constrictive shoe will deform a foot over time or a corset will deform a ribcage. I wondered if Adrienne suffered from this pain as much as I did. Sometimes I still stared into the mirror and hoped that a main character would stare back at me, someone tragic, sleek, and bony, someone whose appearance wouldn’t stunt his soul.

“Itgen’s,” I said. Itgen’s was an ice cream parlor an hour’s drive from my parents’ house, and I had never been there, but its name had the oddness necessary for the game we were playing. I said that an Itgen’s sundae required a long spoon, because it was served in a long, old- fashioned glass, not some kind of cup or dish. I had no idea if this was true.

Adrienne nodded. “That’s the way a sundae is supposed to be.” Barts served sundaes in cardboard bowls, and we agreed that this made their sundaes look like dogfood. I said that the whole point of a sundae was its height. Its height, I said, making a wild, loose-wristed gesture, was supposed to intimidate you.

“Totally,” she said. The gesture she made when she said “totally” was also loose-wristed and wild. “It’s supposed to be so tall that you think you can’t finish it and then you do.” She grimaced. Out of sheer panic—I still feel bad about it—I put up my hand for a high five. We high-fived. After we had done it, we became quiet and ashamed.

We spent the rest of the Orientation Group tour of downtown exchanging information about our families—what our parents did for work, what our houses looked like, the ages of our siblings. We went back to my dorm room and I took cans of juice-flavored seltzer from the squat fridge. When I handed her one of the cans, she sipped from it and reclined in my chair, though it was a desk chair, and didn’t allow for anything like recumbence. We looked at each other. Stooping, I lowered my face toward hers. I could tell, from the way we kissed, that the current passing through us was shared desperation. Either of us would have kissed almost anybody today.

We sat on my bed. It sped my heart to run my hands through her languishing hair, and I felt intense gratitude and admiration, enough to numb the sting of secondariness. It was so good to kiss Adrienne, such an alleviation of sadness and anxiety, that my mind became more lucid than it had been in days, suddenly active, leaping manically from point to point. I wondered if it was the same for her, if she, too, was rehabilitated by the kiss, and was thinking with new clarity about how many of the required courses for an accounting major she should take in her first year, or of the regularity of her period, or of the new season of Atlanta. Thoughts were coming at me rapid fire. Maybe the frat boys and sorority girls made her mad because she was jealous. Did she want to be Queen Cassiopeia of Kappa Gamma? Wasn’t that what love was? Taking an ordinary person and turning them into your queen or president? It would be good, I felt, for Adrienne and me to be rulers of our own insignificant mountain. I touched her face with both hands and put my tongue in her mouth. She’d looked regal, in the van, when she was angry.

She pulled away and tucked strands of hair behind her ears. “Let’s slow down,” she said. She was flushed, blinking, trying to hide her revulsion. I had gotten carried away. It had happened to me before, with girls. The moment I felt that we had made a breakthrough, that we had found a nonverbal language, that the barriers between us had fallen, and we were unified in a single feeling, this turned out to be precisely the moment that I had left my partner behind and slipped away into a private euphoria. It was a lesson I could never remember when I needed to: that the moment of joy in which I believed I had become one with another person was in fact the fall into isolation. She collected her backpack and water bottle. I walked her down the hall to the elevator, for some reason, and the two of us waited side by side at the chrome doors, watching the numbers light up.

The next day, I went home for Labor Day Weekend. When I came back, I worked harder at school than I ever had before, sitting on the second floor of the library, where silence was required, highlighting half of the passages in my political science textbook, drinking Diet Coke and copying and pasting paragraphs from articles into Google Docs that ran thirty pages long. In the aughts, the library had installed a red soundproof booth in the hallway, with the words Cell Phone Zone printed in yellow letters on the side. Sitting inside it on the little plastic chair, I delivered an oral presentation aloud.

The second weekend of September, the temperature dropped twenty degrees. There were blotches of orange in the trees, the sky spat rain for ten minutes at a time, and stiff winds ruffled the purple flowers in the pots that swayed from the lampposts downtown. The cafeteria workers spoke with satisfaction of the New England weather, and the chairs set out on the sidewalk in front of restaurants fell over. Finally, late Saturday night, I went looking for a party, anything to end my solitude. I followed the sound of music.

At the corner where the two fraternities stood side by side, bands of upperclassmen tramped up and down the sidewalk, ten, twelve, fifteen strong. Different kinds of music blared from scattered speakers. Despite the cold, the girls wore shorts or miniskirts, halters or tube tops. They were bright-eyed and unshivering, lit from within. On the porch of Iota Gamma Epsilon, they danced to ’90s R&B, took videos of each other, and played cards on a round table, all beneath a canopy of white Christmas lights. There were Christmas lights stapled or glued to three wooden letters propped against the front of their house, standing in the yard, five feet tall, the iota, the gamma, and the epsilon. A clutch of girls posed in front of them as another girl took pictures, and the letters periodically tipped over, forcing them to shove them upright with their shoulders. A blond boy in a white T-shirt walked up and shouted to the girls who were dancing on the porch, asking to come inside the sorority. When they shook their heads no, he screamed, “I’ll fuck you up, you cracker-ass bitches.” He strutted down the sidewalk with his shoulders thrown back, tossing his great white head like a horse, running his hands through his golden hair. “I’ll fuck you up for real, you hear me, you cracker-ass bitches?” He continued to issue the threat, over and over, always at the same incredible volume, and then he turned the corner down the hill and vanished into one of the smaller houses midway down the slope.

I followed his path down the hill, swerving around the roving groups until they thickened into a mob. Someone shouted above the music, “They’re shutting it down, so we’re moving to the parking lot.” Police SUVs rolled up and down the street, flashing their blue lights as the crowd flowed around them. “She sent me a video of her pussy, and her ass, actually,” someone said. To my right, inches away, a boy had lifted his shirt to show his injuries to his friends: “Look at this badboy here,” he said. “And look at this little badboy, getting his bleed on.” Every house had a door swinging open to disclose a blue or strobing light, every house had strands of Christmas lights blinking in the windows. “I’m not going to lie,” someone said. “I’m not going to front.” Cops walked up and down the hill with their hands on their belts. Boys fell and were picked up by the boys on either side of them. A firetruck trundled by, red lights flickering out of sync with the blue lights of the police, and firemen trooped single file into a house on the corner. The scene looked like a protest without the cardboard signs.

A dark-haired girl with sparkling eyeliner reached through the bodies, stumbling, and took my hand. “Hi,” she said, grave, and her friends peeled her away. A trio of girls reunited, screaming like mountain lions by way of greeting. This crowd would never have been tolerated on the Common, even though the town tolerated all manner of demonstrations, drums, chants, dancing, singing, a hundred spectacles of nonconformity. The Greeks didn’t want to be in the right. Their screaming was only a way to say that they excited each other. That was rebellion, here. They’d figured it out.

I went into the house to the left of the one with the fire in it, and some of the boys gave me hard looks but nobody stopped me. It was the beginning of the school year, everyone was back together, and the mood was celebratory.

A sheet bearing the black-and-yellow Ferrari stallion rampant was draped over the front window. There were spinning green flowers projected on the wall. The music shook the floor. A girl sat on the shoulders of two boys, chugging punch the boys scooped from a storage tub bedazzled with glow-in-the-dark stars. I lapped the room a couple times, slipped through the dancers without speaking to anyone. People turned and flashed looks at me from the safety of their circles. I leaned against a wall, wearing a smirk whose fraudulence I felt as a physical strain in my mouth and eyebrows. Soon I dropped it and let my face assume an expression I knew was one of pleading.

After perhaps thirty seconds there was a tap on my shoulder. It was one of the Deltas—I knew from the letters on his sweatshirt—and he held a cup of beer in each hand. “Would you like one of these?” he asked.

The phrasing of the question was oddly formal. He sounded like a cater-waiter with a tray. His eye contact, too, was strange, unwavering but not challenging. I accepted. We raised our cups and drank.

His pledge name was Smackhead, he said, as he hailed from the opiate-afflicted state of New Hampshire, and he’d had it for three years now. But his real name was Dan; I could call him Dan. He still lived in Delta, even though he was a senior and some of the brothers in his class had moved farther from campus. He couldn’t imagine leaving, especially now that he had a single. He loved it there.

I thought I knew, then, what was going on: It was pledge season, and he wanted to recruit me. That would account for his manner. The techno on the stereo faded, and a melancholy slow jam began. The wounded singer denounced a lover who’d been untrue. The response from the crowd was immediate: girls who’d been crouched low to the ground unfurled themselves and swayed with their arms in the air; boys didn’t sway so much as wobble, flapping their arms mournfully like great endangered birds of prey. Even the boy in a MAGA cap, so drunk he was seated on the floor, did an upper-body swivel that evoked the Twist.

“Don’t you love how everyone’s so much happier with a sad song on?” asked Dan/Smackhead. He rubbed one of the buttons on his polo shirt with his thumb. “It makes me feel like the happy songs are just there to let the sad songs destroy you.” I asked him what he meant. He squinted at the ceiling. “This song wouldn’t be so good if every song they played was sad. You need most of the music to be everybody-dance-now for the real songs to connect.” He made a loose fist and jabbed my solar plexus very gently, and then opened his hand, so that it suggested an explosive projectile connecting with its target and so that his fingers stroked my chest. It was when he did this, and I laughed, that I first saw flickers of meanness on the faces of some boys on the dance floor.

He asked me questions and scratched at his hair, short fine quills. No matter how simple my answers, he seemed to regard them as profound. It made sense that I was from Long Island and had excellent taste in music, he said, because Long Island was next to New York City, where people were sophisticated. It was no wonder, he told me, that I’d been spending all my time in the library, given that I’d grown up so near to a center of learning. He’d never heard of any of my favorite movies, so he wrote down their titles in his phone, as the titles alone, he said, were intriguing. He’d known at first sight that I would prove intriguing, because of how differently I dressed from everyone else here, he said. People like me, he assured me, didn’t come to parties like this one. No one had ever offered me so much praise in such a short amount of time. It was possible, I decided, that, while some girls had welcomed my overtures, no girl had ever actively pursued me. This dizzy state was surely the state of being pursued. I felt that it was making me stupid, but in an interesting way. All I had to do was state a fact about myself, and he would labor to find specialness in it. It was like playing fetch, a game where you stood there feeling imperious and watched the other player work. It was also fetch-like in that I got tired of it before he did.

I Hate Cassiopeia

I was about to excuse myself and leave when one of the guys who’d been on the dance floor only seconds ago passed us on the way to the keg and checked each of us with his shoulder, one after the other. He knocked us into the wall, spilling our beers down our shirts. We shouted after him for an explanation, but he only stopped when he reached the keg. He took a fresh cup from the stack and leered at us as he pumped, his cup tilted 45 degrees to minimize foam. He was broad in the shoulders, deep in the chest, with the kind of forearms that betokened participation in contact sports. Two other boys standing near the keg watched us and laughed, staring at us with open contempt. Fuck them, how dare they try to frighten me? My thoughts spiraled off into the usual fantasies of fistfights, retribution. Then it occurred to me that there was something I could do to prove that these subhuman giants had no say in my behavior, that their display of power meant nothing.

In this one quarter-mile of town, I realized, this one three-block radius, running off with the boy beside me would be an act of defiance. I pawed the front of his shirt where the beer had soaked through, as if the flesh of my hand were absorbent. I looked up at him—Dan was a little taller than I was—and put my thumb on the button he’d rubbed with his own thumb.

“This place is a shithole,” I said. “Do you want to go to Delta, and show me around?” I danced in place and closed my eyes. I had never done those two things at the same time. My voice sounded docile and naive. “Maybe you can show me your room.”

He turned and looked at our enemies, tapped his foot, folded his arms. Suddenly, he looked frightened. “Be patient with me,” he whispered in my ear. “I’ve only ever done this with girls.” We hurried across the dance floor to the door.

We didn’t do some of the things we could have done, because neither of us knew what he was doing. We were both clumsy, that night. But in his cramped, overheated bedroom, with the pounding of the bad music outside, and the taste of bad beer in my mouth, and the knowledge that the beer on our clothes was there because someone had wanted us to know that we were trash, and the violent idiocy of the chatter on the street, and the lawn below us covered with litter, I liked everything about him. He could do no wrong. I forgot who I was, and what I stood for, and I would have done anything he asked me to do.

Stjerner I Cassiopeia

If you like this article, please subscribe or donate to support n+1.